photo: Mark Dubois and Marty McDonnell on an early trip down Cherry Creek.

It’s easy to take self-bailing rafts for granted, until you don’t have one. Anyone who has drifted headlong for a horizon line while frantically tossing buckets of water overboard knows the feeling-pure panic.

Cherry Creek is no place to be in a water-logged boat, so it’s little wonder that California’s landmark Class V run became the birthplace of the modern self-bailing raft. Marty McDonnell began guiding self-bailers on “The Creek” in 1982, nearly a decade after making the first raft descent in the spring of 1973 with Walt Harvest. Later, McDonnell helped develop the revolutionary self-bailers, and his efforts served as the bridge between concept and fruition. McDonnell will be the first to tell you, however, that the evolution started years earlier, with innovator Bryce Whitmore.

Whitmore ran rivers in the 1950s, when the only specialized equipment was homemade. When Whitmore deemed wood and canvas kayaks too cumbersome for the rivers he was running, he built a fiberglass kayak, one of the first in North America. In 1961, he made an exploratory descent of Kings Canyon with paddling icon Roger Paris. When they finished that iconic run, Whitmore got news that his house had burned down. He promptly quit his job as a chemist, and started his own commercial rafting venture.

For rubber, Whitmore used military surplus inflatables originally designed as floating docks for seaplanes. He boldly cut the 24- foot tubes in half and glued them back together, creating a sort of giant air mattress with oars. The boats were crude, but unlike every other river craft of that time, they didn’t need bailing.

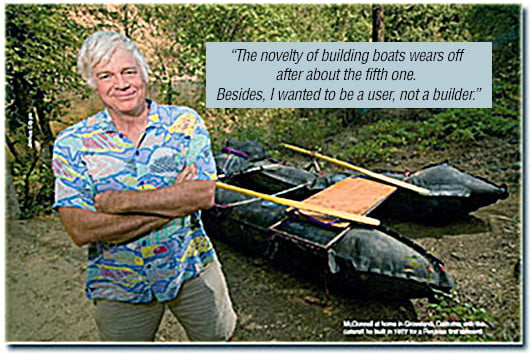

One of Whitmore’s guides in the ‘60s was McDonnell, who regularly ran different versions of the surplus rafts, known as “Super Sports” and “Huck Finns.” By the late ‘70s, McDonnell was taking the boats down Cherry Creek, and tweaking the designs to better suit the steep riverbed. When a rubber materials supplier began to falter, Marty bought his own bulk neoprene, apprenticed with a lifeboat builder, and started making his own rafts. He strove to create a Huck Finn that you could sit inside of rather than simply riding like a bronco. Despite McDonnell’s enthusiasm for design however, raft production wasn’t for him. “The novelty of building boats wears off after about the fifth one,” he says, “Besides, I wanted to be a user, not a builder.” Enter Glenn Lewman-the builder.

One of Whitmore’s guides in the ‘60s was McDonnell, who regularly ran different versions of the surplus rafts, known as “Super Sports” and “Huck Finns.” By the late ‘70s, McDonnell was taking the boats down Cherry Creek, and tweaking the designs to better suit the steep riverbed. When a rubber materials supplier began to falter, Marty bought his own bulk neoprene, apprenticed with a lifeboat builder, and started making his own rafts. He strove to create a Huck Finn that you could sit inside of rather than simply riding like a bronco. Despite McDonnell’s enthusiasm for design however, raft production wasn’t for him. “The novelty of building boats wears off after about the fifth one,” he says, “Besides, I wanted to be a user, not a builder.” Enter Glenn Lewman-the builder.

As a teenager, Lewman had seen one of Whitmore’s original Huck Finns on Oregon’s Rogue River. As the boat drifted past, a friend told Lewman, “That’s the boat I’d get, because you don’t have to bail it.” The notion simmered for over a decade before Lewman started SOTAR in 1980, working with McDonnell’s feedback, Lewman and the SOTAR team began the inflatable floor experiments.

Their first design included a wooden floor that transformed into a raft-carrying box. It sank. The next incorporated an air mattress attached beneath the wooden floor. It floated, but was brutally heavy. Finally, they scrapped the wood for a lashed-in air mattress. Water coming over raft sides would flow out through the lashings, and the first true self-bailer was born. “From that stage, it took about four more refinements until we got it basically right,” Lewman says. Another two years passed before the self-bailing paddle rafts were on the market in ‘84. Lewman remembers a skepticism that is laughable in hindsight. “People that had never used them had a million reasons why they wouldn’t work,” he remembers.

A quarter-century later, self-bailing rafts are the industry standard, and rafters rarely experience that feeling of drifting, helplessly, toward a misty horizon.

from Canoe & Kayak Magazine – December 2009